A MIGRANT'S LIFE

Idomeni, Thessaloniki (GR), Mar 2016. Since the economic crisis struck at the beginning of the new millennium, fundamental principles of the European Union have often been challenged by both conservative and nationalistic policies of the single states, as well as controversial collective decisions. Today the strength of these bonds is once again proven by the European migrant crisis, which for the EU Community takes the shape of an identity dilemma in front of the Charter of the Union’s founding values.

This kind of situation only seems to be the last of a series of recent hesitant behaviours, such as during the Ukraine-Russia crisis, the defaulting of Greece, and the closure of the EU borders to undocumented migrants. In this scenario, the signing of the EU-Turkey deal is certainly received with bewilderment but no surprise. While the deal is directed at controlling and managing the arrival of thousand of asylum seekers in Europe, it instead takes away from that framework of principles at the heart of a united and strong European community. Thousands of lives are now at stake, bound to become bargaining chip in favour of political and economical interests between Europe and Turkey.

So far, the EU has taken debatable stances in the management and decision-making process of this humanitarian crisis. Brussels’ recent decision to shut Europe’s internal and peripheral borders in order to stop migratory routes only led to a worsening of the emergency, stranding as much as 50.000 refugees in Greece alone. This situation becomes evident in Idomeni, a small Greek village in the picturesque countryside along the border with Macedonia. This is where an important segment of the Balkans migrants’ route passes through, along the Thessaloniki-Skopje train line. However, since November 2015 thousand of people have found themselves stuck here, in the mud and harsh weather conditions of this mountainous landscape, helpless in front of the barbed wire and fencing installed by Macedonian border patrol forces.

In this era where free movement has become more and more everyday practice, this solid border rises to remind us of those intangible lines which we often only see drawn on maps, which we unwittingly dismiss and overlook. However, such boundaries symbolise much more to people seeking refuge from conflicts and persecutions. They turn into the invisible walls of an impenetrable fortress called Europe, at whose feet lie hopes and dreams of a new life. And this piece of land which normally holds little or no strategic importance becomes a site of struggle to claim the right to a respectable future. At the same time, Idomeni comes to represent for the EU the focal point to a number of crucial issues concerning the management of migrant fluxes. All this becomes reality in the refugee camp which has spontaneously come to life in front of the state border line.

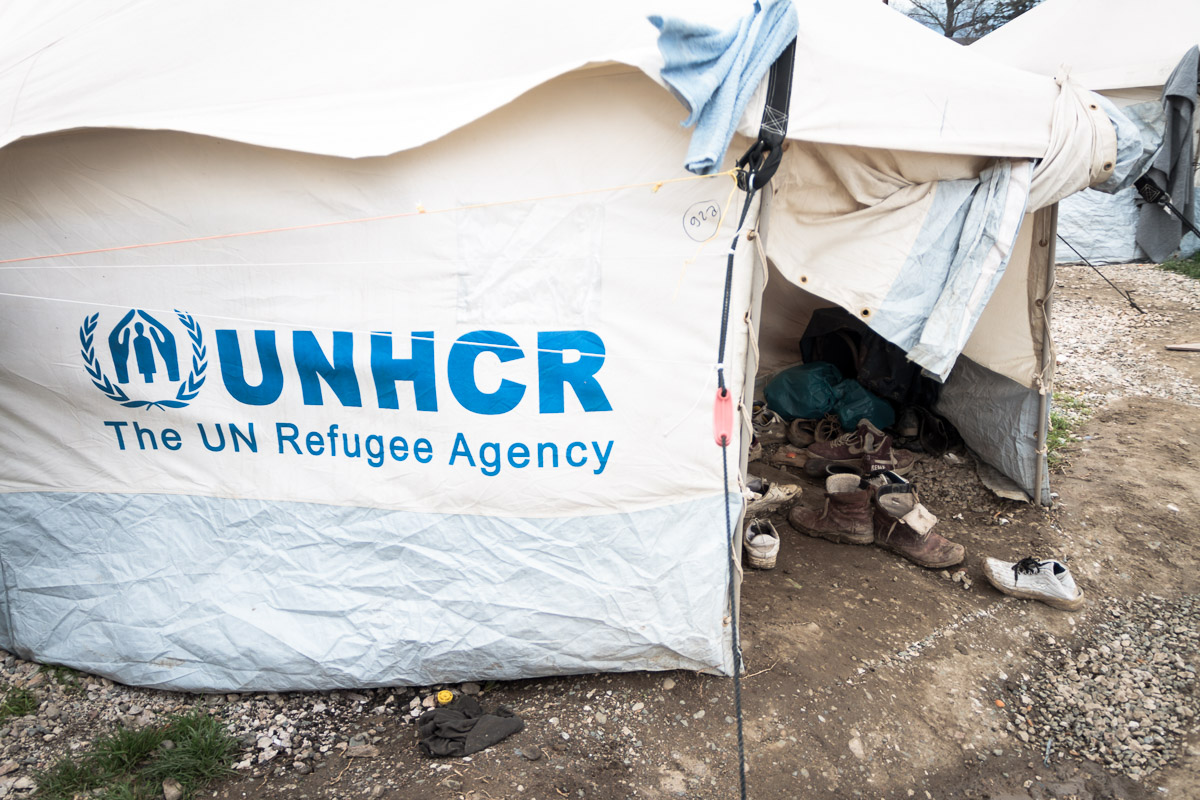

In the camp, NGOs exhaustively work lacking any kind of support from local authorities or the central EU administration. They provide temporary emergency accommodation, food and first-aid to more than 12.000 asylum seekers. Those more lucky live in house-tents of different sizes, capable of hosting from a few people to hundreds of them depending on their size. While the former can offer some more privacy, the latter simply consist of large open-space structures filled with rows of bunk beds, where the only real comfort is that of a big power-charging hub.

It is by one of these stations in a 150-beds tent that live Ola and Noora, both from Aleppo and respectively 25 and 29 years old. Ola had just obtained her bachelor in Mathematics when she had to flee from Syria three months ago after a Russian bombing destroyed her house. Noora was instead a dentist nurse in her home-town before the revolution began. She managed to dodge the shellings but eventually decided to leave the country due to her fears of falling into the hands of ISIL terrorists, well known for their barbaric actions against civilians. As they both say, the war has taken everything from their lives: their houses, their jobs, their families – the hope for an ordinary and serene life. They have now been stuck here for a month waiting for Macedonia to open its border again, in order to attempt crossing the Balkans and reunite with their respective relatives living in Germany. Eventually they hope to settle and resume their living, Ola says perhaps continuing her studies and earning a PhD.

Not too far, in UNHCR’s “Tent 3” lives Adnan, 49 years-old from Syria, former rig engineer for a Syrian oil company. He has arrived in Idomeni three months ago with his two children, and only recently they managed to get a place in the bigger house-tent. He explains how terrible the situation in Syria is, where human life is totally disregarded for and people are brutally killed every day. He shows a picture on his phone of his third son, aged 17, who has been detained for the last two years in one of Bashar al-Assad’s jails in Damascus accused – Adnan says falsely – of colluding with the Syrian Free Army. He further explains how the current regime has turned Syria into a land of conquest for terrorist groups led by ISIL as well as international super-powers trying to establish their political influence in the Middle-East. Eventually, who pays the price for all this is the civil population, which is forced to flee and even then cannot find anything but shut doors. Looking at his children, Adnan finally comments on how difficult the situation in Idomeni is for them, with lack of basic needs such as food, hygiene and warm shelters.

The number of children and unaccompanied minors present in Idomeni amounts to almost half of the total population of the camp. Children can be seen everywhere, playing and running among the interminable queues for the distribution of food and essentials. However, their seemingly carefreeness is often only superficial, which is especially evident in older teenagers who have been compelled to become young adults before their time. As some of them reveal the scars this war has left on their skin, many others conceal their traumas deep in their minds. Indeed, many people who arrive in Idomeni are often not only in need of a bed, roof and food, but also of psychological support. However, this aspect of personal wellbeing often fades into the background due to the invisible nature of the problem, although post-traumatic disorders and the large amount of stress procured by this kind of living play a central role in Idomeni. Eventually, this affects also volunteers who come from every part of the world to offer their help.

Lorty currently works for Forgotten In Idomeni, an independent and international NGO coordinated through its large community based on Facebook. "We are now receiving several enquiries per day and over 150 people registered to volunteer. The flexibility they demonstrate and the way that some have just stepped up to make decisions and take responsibilities, as well as establishing supportive relationships, is admirable" Lorty says, calling this "a do-it-yourself mentality at its best". However, while big organisations such as UNHCR and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) can be more flexible, independent NGOs can get more easily tied up in red tape. Lorty adds that "the way volunteers can manage to look after themselves, take initiative, get stuck in, is quite amazing. But I do worry sometimes about how sustainable all of this is", referring to the significant stress volunteers undergo due to the burden of the daily work and the current political situation. "When we experience just how intransigent states can be and how heavy the struggle for human rights is, it can be very affecting".

But NGOs are not alone and support also comes from the Greek population which only feels the urge to contribute with its help. This self-call-to-action can be described by the Greek concept of philotimo, a word which cannot find direct translation to English but can be identified by a series of virtues such as honour, dignity, respect and sense of duty. Philotimo is a high moral principle originating from Ancient Greece, a foundation to good living and social interaction. It is indeed this mentality of union and togetherness that pushes Greek citizens to share their roof and food with entire families of refugees.

This is also what Lorty means when she says that this grassroots organisation is eventually proving fundamental in this situation as a complementary solution to the hesitant behaviour demonstrated by institutions. In this regard, virtual spaces have been pivotal in bringing together an international community as a response to this stalemate. Indeed this is one of the first humanitarian crisis where smartphones, internet and social media are playing a fundamental role both in the coordination of aid and assistance, and in keeping migrants in touch with the rest of the world and their relatives. Just like Forgotten In Idomeni, dozens are the self-organised NGOs that are based on social media and use crowd-funding in order to fill the gaps that the EU has left exposed in this crisis. The unprecedented level of awareness offered by today’s technology has therefore become central in building a solid humanitarian response.

Unfortunately, the effort put in place is still not enough compared to the amount of resources required and number of migrants arriving daily in Idomeni. The camp has now expanded and has already reached the nearby train station, where the main building and the empty cargo carriages are used as improvised shelters. However, the majority of the camp’s population resides in small camping tents pitched along the rail tracks used daily and in the fields all around. Eventually this situation only comes to benefit smugglers, whose business is now thriving along the border.

As in many other places along the Route, in Idomeni the face of a smuggler is that of a taxi driver, a street vendor, a casual citizen. Sulaiman is 37 and is travelling with her wife and children. He explains how prices are very high, usually not cheaper than €350 per person to get across the border. A price to be paid in advance often with the risk of being scammed, kidnapped or beaten up and robbed, not only by smugglers but police too. A risk worth taking in alternative to the long, extenuating and not always guaranteed asylum application process. While he tells his story, he shows the video shot with his smartphone on the overcrowded rubber dinghy that took him and his family across the sea from Turkey to Kios. In that instance he had to pay €2200 a local trafficker, who once reached international waters forced them at gunpoint to continue alone and then escaped on an accomplice’s boat.

The extremely difficult situation is further worsened by the lack of organisation and order, which make fertile ground for gangs to easily conduct criminal activities. Refugees do not feel safe living even inside the bigger and more protected house-tents, where they say at night people come to steal and intimidate. To make things worse, the presence of many different ethnic backgrounds in such a restricted space becomes cause for discrimination, scapegoating, and eventually conflict.

Under these circumstances, refugees strive to survive how they can, often trying to find ways to earn money in order to buy food and other essential goods on the thriving and highly expensive internal black market. Christopher (as he wants to be called) is a 27 years-old Iraqi university student. With his broken English, he explains that he fled Mosul fearing the ISIL occupation, just another nightmare after Saddam Hussein's regime and the subsequent conflict and civil war. He has travelled for months only to arrive in Idomeni and find out it was too late. Now he is waiting as everybody else, selling the few personal belongings he has in order to get daily meals. His final destination his Finland, where he would like to settle and become a professional basketball player, a dream that in Iraq he could not pursue due to the restrictive society.

For asylum seekers the deal that Europe signed with Ankara is predicted to be disastrous by NGOs and humanitarian associations. Under the current circumstances, refugees are going to become goods to be traded for money and concessions. Migrants who do not qualify for asylum in Europe will be returned to Turkey, which will also receive a payment from the EU for each deportation. In exchange, the latter will accept one Syrian refugee up to a total maximum of 72.000 people until December 2020. Furthermore, the deal includes for Turkey the disbursement of €6 billions intended for the management of the migrant crisis, the “re-activation” of negotiations regarding its EU membership, and the easing of visa restrictions.

However, it is evident that Turkey alone will not be able to deal with the amount of people still fleeing from Syria and neighbouring countries, in addition to those who are going to be deported back. The same stands for Greece, which in the meantime has become a limbo, a liminal space between two jurisdictions, which ironically is not even receiving any financial help from the EU. These are countries which are already struggling with their own internal problems in matter of politics and economics, without mentioning the major issues concerning Turkey in regard to fundamental freedoms and its fourty-years long conflict still going on in the Kurdistan region.

As a consequence, both NGOs and asylum seekers are actively showing their dissent against a deal that they say goes against international law and fundamental human rights. The UNHCR, MSF, Save The Children, the International Rescue Committee and the Norwegian Refugee Council have already declared that they are halting operations in 27 camps and detention centres around mainland Greece and its islands. In the meantime migrants in Idomeni are holding hunger strikes and daily demonstrations inside the camp as well as outside. Few days ago hundreds of them symbolically blocked the motorway traffic, closing in their own way the border with Macedonia. But exasperation is building up and some warn of committing to desperate acts of self-immolation, as it happened few days ago when two migrants set themselves on fire.

This is an unprecedented situation, the exodus of not just people but of a whole society. Most of them not interested in permanently settle in Europe, but rather to go back to their homeland once the war will be over. The creation of an impenetrable European border is not only a dystopic solution, but neither a short nor a long-term one capable of improving the current situation. As it has already been proven, the flow of people cannot be stopped with barriers or agreements, as these eventually end up benefiting the same criminal organisations Europe is trying to fight off.

From the perspective of how things are today developing in Europe, Greece, Idomeni, one is led to wonder whether it still makes sense to talk about this Europe as a cohesive community of nations, able to come together and cooperate bypassing the single’s interests and priorities. As a result, Idomeni is slowly becoming for many, both asylum seekers and EU citizens, the emblem of a broken European dream. In the meantime, refugees are not willing to give up and many think of bypassing Macedonia through Albania or Bulgaria. Is this going to be the next chapter to this odyssey?